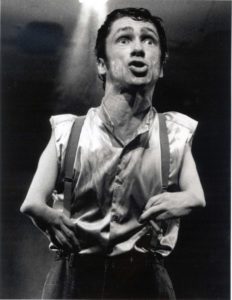

Mat Fraser by Photographer Ashley Savage

By Allan Sutherland

One of the interesting discoveries of the transcription poetry process has been how well the poems lend themselves to live reading. (The reason may be the accuracy with which the process preserves the individual voice of the person interviewed.)

I saw this demonstrated at DAiSY Fest 2014 when I gave a reading from Proud, my series of poems from the words of Jennifer Taylor. As a black woman with learning disabilities, Jennifer is a very different person from me. But her voice came powering through in what proved to be a remarkable evening.

So, at a recent D4D meeting, when we wanted to give the rest of the team a sense of what was happening in Electric Bodies, it was natural to give a reading from Thalidomide Acts, my set of poems with Mat Fraser. This may not be a standard form of academic presentation, but I’m not an academic, and we’re not a standard team.

Responses were good. Martin Levinson, our Principal Investigator stated that hearing the work read has resolved doubts he?d had about whether the process raised ethical concerns. Mary Brydon-Miller noted how there were two distinct voices present. (I was pleased by that. People don’t always get that my voice is present in the work as well as that of the poem’s subject.) Lucy Burke, being a literature academic, was strongly interested in how I made the editing decisions that take the work from transcription to poems.

I hope they’ll explain these thoughts themselves in further posts.

Some reflections on Thalidomide Acts

Allan’s reading prompted lots of questions for me. I have written about life-writing and biography in several different contexts from early twentieth century women?s writing and activism to contemporary memoirs about dementia. I have always been interested in what isn?t included in the process of narrating, transcribing and editing.

I am thinking about all the material, ideas, sentences, words, passing thoughts and unfinished business that doesn?t wind up in the final piece but that haunts it as a set of unrealised possibilities; those cuts and deletions whose history it is impossible to discern in the finished text.

I think that this is an important thought to have in relation to a project such as ours which is so centrally concerned with the mechanics of exclusion and invisibility and with the formation and deformation of community.

What do we think matters about the telling of a life story, how do we form the morass of experiences and interactions that constitute our lives into a narrative? What might an exploration of the material that doesn?t end up in the final poems tell us about the choices we make and what we think is and isn?t important?

I would want to explore how these transcript poems produce a portrait of disability art and the disabled artist ? I am interested in whether there is an orientation around particular moments and experiences, for instance, the epiphany rather than the everyday. Is there some kind of gravitational pull to keep some anecdotes and discard others?

To what extent do the interviewees draw upon literary conventions and genres to construct their own histories ? the heroic or the comedic (or both) for instance? How does the transformation of the text into poetic form mediate our responses and encounters with the material?

What place do other people and relationships have in these narratives and the process of turning them into transcription poetry? Finally, I am also interested in the question of who ?owns? the poetry and what authorship might mean in this context? All these questions have an ethical dimension which I think we need to think through.