Image from D4D cultural animation workshop.

On a brilliantly sunny day in April it seemed somewhat ironic to be entering a darkened gallery space to explore A Certain Kind of Light. Although I was slightly resentful to be missing out on bathing in those precious rays, I was soon immersed in the current exhibition at The Towner Gallery and intrigued by the subject. However the theme was somewhat tenuous, these works often spoke more about those moments ‘in between’ and where things cease to exist, than purely about our relationship with light.

The Anish Kapoor work bounced light around polished steel but represented a void; a black hole that threatened to swallow us up. There was also a very physical sense of absence in the resin casts of Rachel Whiteread, making solid the negative spaces found under chairs the hiding places of her childhood. John Riddy’s Photographs were concerned with architecture and space but most particularly the ‘absence of human activity’.

The more I experienced the exhibition the more it resonated with my own practice and in particular my arts led research on the D4D project. Theatre Director Sue Moffat and I have been exploring the Presence of Absence: what happens when something, or in particular, someone of significance is removed. What fills the void and what does that void feel like?

This exploration is most concerned with the ethical dilemmas of genetic screening. Soon it will become much more common place to routinely screen for a number of genetic ‘abnormalities’ but as we start deleting those individuals from our collective society what will that void look like and what will it mean to us in terms of what we might lose?

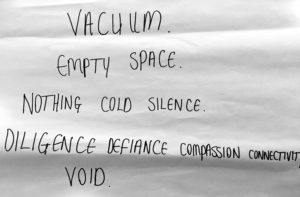

The Poem is a Cinquain based on the Presence of Absence

The previous weekend at Graeae Theatre, Sue and I lead our first cultural animation workshop with participants asking them to explore through play and objects, the fundamental human drive to create order out of chaos. We also started to touch on what the presence of absence meant to them.

Contemplating A Certain Kind Of Light reaffirmed to me the way art has the capacity to demonstrate the very physical experience of negative space, the moment of nothingness but pregnant with possibilities.

The final work in the Towner exhibition brought to my mind two symbolic objects. The monolith in 2001, a mysterious object perhaps capable of providing knowledge and understanding of what it means to be human; and my most recent work Pandoras Box. The work by Shirazeh Houshiary entitled Cube of Man stood like a futuristic totem pole bridging the void between heaven and earth. Made from the same materials as Pandoras Box (gold leaf and lead) it seemed to be preoccupied with similar concerns ‘the marriage between the spirit and the body’.

It lead me to contemplate whether in that space between man and God has science stepped in to fill the void, the negative space. Is the utopian future that science offers us where ‘suffering’ is eliminated, in fact a mask for dystopia, where we risk loosing in that negative space the very essence of what it means to be human. If light is the best of humanity then it is perhaps a worry to be heading towards the darkness.